Bourbon Whiskey - Tennessee, USA

TENNESSEE’S DISTILLERY DAMES

Simon Urwin delves into the heart of Tennessee whiskey, and meets some of the women who are responsible for it.

“I’ve been all kinds of badass,” says Kendra Anderson with an earthy laugh. “First as a bartender and a bouncer, then a bail bondswoman and a bounty hunter.” This last involved belly-crawling under a fence in a mini-skirt in hot pursuit of a court fugitive – a taser in one hand, a gun in the other. “That kind of action is all in the past though,” she says. “Now, I’m all about being badass with whiskey.”

‘WOMEN ARE MADE FOR IT, WE’VE GOT MORE TASTE BUDS THAN MEN; MORE OLFACTORY NERVES TOO – THAT’S IMPORTANT WHEN IT COMES TO PRODUCING FLAVOUR PROFILES’

Anderson is chief distiller at Leiper’s Fork Distillery – one of around 40 distilleries in the state that specialise in making whiskey – a tipple as closely linked with Tennessee as, say, bourbon is with Kentucky, or chardonnay with California. Anderson is also one of an increasing number of women helming high-end whiskey production here, having first become fascinated by distillation during her shifts as a bartender.

“Women are made for it,” she says. “We’ve got more taste buds than men; more olfactory nerves too – that’s important when it comes to producing flavour profiles.” Anderson also sees whiskey-making asw inherently maternal. “You give so much of yourself. And it takes time. As soon as I start tapping those barrels, it’s emotional, like giving birth to my own children.” She tells me that she can literally feel distilling in her bones. Born a Stewart, she traces her family tree back to Scotland, from where, centuries ago, her ancestors crossed the Atlantic carrying their pot stills, and settled in what is now Tennessee after the lands west of the Appalachians were opened up by frontiersman and liquor trader Daniel Boone.

“Back then, distilling was a hearth skill done exclusively by women,” she says. “Those pioneer women were tough and resourceful. These days is no different. Only this morning I was f ixing problems with the steam boiler and the mash cooker. I guess I’m just one in a long line of women being a badass and a kickass in the world of whiskey.”

Women have indeed played a vital role in the history of the craft dating back some 2,000 years ago to Mary the Jewess, an alchemist from Alexandria, Egypt, who invented a copper distillation chamber – an early version of the stills that are in use to this day.

By the 1400s, distilling had spread to Europe, and by the early 1500s spirit-making was in full swing, with many women across the continent cooking up ‘eau de vie’ (‘water of life’) as it was known in France, or ‘aquavit’ in Scandinavia, and ‘usquebaugh’ in Gaelic-speaking Scotland and Ireland – where it was commonly abbreviated to ‘usky’ or ‘whiskie.’

It is the Scots-Irish who are often credited with introducing whiskey-making to Tennessee. Yet, because of widespread illiteracy and prejudice at the time, little was documented of the contribution of women settlers to distilling culture, let alone other significant figures, including the land’s original inhabitants.

“Without the Chickasaw and the Cherokee people, we wouldn’t have our world-famous corn whiskey,” says author and historian Drew Hannush. (A true Tennessee whiskey must contain 51% corn.) “Corn is not a native species. It had been brought up from Mexico by Native Americans who cultivated it so successfully that when European colonists arrived, they found a bounty of grain. The soft starches in corn were perfect for making whiskey.”

An even greater omission is the contribution of African-Americans. As the hearth skill grew into an industry it was deemed ‘man’s work’ and soon distilleries were adorned with the names of their white male owners. But it was enslaved black men who made up the majority of the workforce. Crucially, they were often the lead whiskey-makers too, drawing upon age-old skills for brewing corn and millet beer, and distilling fruit spirits and palm-sap liquor; skills that had been carried to the New World in the slave ships from West Africa.

One of those men was Nathan ‘Nearest’ Green, the first African-American master distiller on record, who in the mid-1800s taught a young Jack Daniel how to make whiskey. When entrepreneur Fawn Weaver stumbled across the extraordinary story of an enslaved man’s role behind the world’s best-selling whiskey brand, it inspired her to shine a light on his long-forgotten legacy.

“The idea for a simple commemorative bottle quickly grew into a greater ambition: to open a distillery to honour his name and his talent,” she says. The Uncle Nearest brand has since become the fastest-growing independent American whiskey, and one of the most-garlanded whiskeys in the world.

“With every sip, people start to share his story,” says Weaver. “That starts to put right a wrong. For far too long, African-Americans have been portrayed as unintelligent, unskilled. But we’re the opposite: we are creators, innovators, people of excellence.”

Uncle Nearest’s multi-award-winning master blender is Victoria Eady Butler – Nathan Green’s great-great-granddaughter. She tells me that Green’s presence can still be keenly felt in every step of her work, particularly during the mellowing stage known as the Lincoln County Process, when whiskey is filtered through sugar maple charcoal to remove impurities and give it its smoothness.

‘BACK THEN, DISTILLING WAS A HEARTH SKILL DONE EXCLUSIVELY BY WOMEN, THOSE PIONEER WOMEN WERE TOUGH AND RESOURCEFUL. THESE DAYS IS NO DIFFERENT’

“For centuries, West African people used charcoal – not for alcohol, but to filter and purify their water,” says Butler. “So, while Nathan Green didn’t invent the process, he took it and perfected it.”

The Lincoln County Process has since become a defining feature of Tennessee whiskey, and a key factor in what makes it distinct from any other spirit in the world. “That’s why we consider Nathan Green the godfather of Tennessee whiskey.”

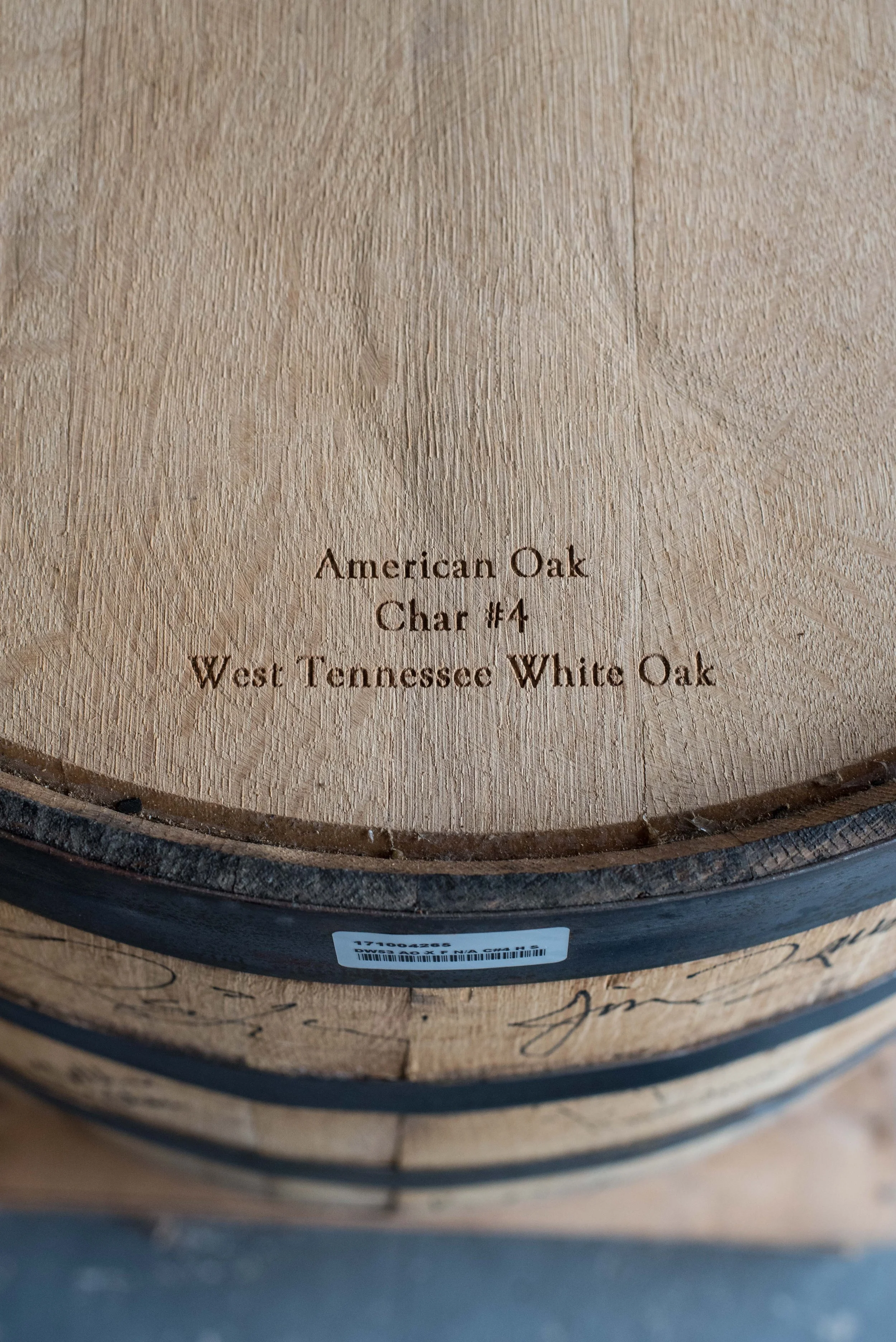

In the era of Nathan Green, whiskey was booming across Tennessee from the wealth of natural resources for spirit-making in the state’s three distinct regions (represented as white stars on its iconic Tri-Star Flag.) From the east: sugar maple trees for charcoal; from the midlands: grains for the mash bill; and from the west: white oak for barrels that were shipped down the Mississippi River from the Ozark Mountains.

A nexus of river and railroad traffic, Tennessee whiskey could reach markets near and far, and it soon became one of the top three distilling states. Manual workers moved in their droves to the big cities of Memphis, Nashville and Chattanooga to find employment in the distilleries and associated industries – including gristmills, cooperage f irms and wholesalers. As a result of the urban drift, there was a proliferation in tavern culture; drinking and gambling too. The social problems that ensued eventually led to the ratification of the 18th Amendment (National Prohibition) in 1919, banning the production, sale and transportation (but not the consumption) of all alcohols.

“The law didn’t stop women though,” says Tiana Saul, head distiller at Chattanooga Whiskey. “They ran illegal speakeasies and secretly made moonshine and bathtub gin. They were expert bootleggers too.” Women smuggled bottles of booze in Bibles, inside their blouses, even under babies in pushchairs: places where male Prohibition officers wouldn’t be allowed to search. “If it was illicit, there was always a woman somewhere in the mix.”

Tennessee remained under Prohibition until 1937, by which time whiskey’s image had tarnished and become more closely associated with alcoholism and organised crime. But its fortunes were revived by Ol’ Blue Eyes himself: Frank Sinatra, one of the most popular entertainers of the mid-20th century. Known for his love of whiskey, Sinatra began to appear on stage with a glass of Jack Daniel’s served 3-2-1-style: three rocks, two fingers of Jack, and a splash of water. He was even buried with a bottle of his beloved Old No. 7 in the coffin beside him.

“Tennessee whiskey and music have always been uniquely and intimately linked,” says Devin Walden, head distiller of Big Machine Distillery in Nashville. “It’s what sets it apart from other states, like Florida, where drinking is synonymous with vacation. Here it’s all about conviviality, celebration, bringing people together over a glass of something.”

The relationship between whiskey and music is said to have begun with the Scots-Irish. Clannish people, they settled in small, isolated communities across the state and had to make their own entertainment of an evening by playing traditional music around the still. The whiskey jug itself then became the centrepiece of the popular African-American jug-band scene, a homespun form of instrument-making and music that became wildly popular in Memphis and is directly linked to the development of blues and rock n’ roll.

“The two feed into each other in terms of energy and ideas,” says Walden, who, with a padlock neck chain, sleeve tattoos and slicked-back hair, brings her own rock-chick vibe to the whiskey-making process. “It means distilling is not held back by tradition or nostalgia here. Yes, Tennessee whiskey has to fulfil a certain set of rules and regulations, but thereafter the sky’s the limit.”

In recent decades, the state has seen an explosion of small craft distilleries alongside the big international brands, a development which has opened up the industry to more women, many of whom have come to distilling via highly eclectic routes. “It results in more playfulness,” says Tiana Saul, a San Francisco transplant who originally studied cultural anthropology and dance.

Saul, who describes the job of head distiller as a mix of “magician, alchemist, scientist and artist,” goes on to tell me that at Chattanooga Whiskey she has experimented with a dozen types of yeast, 20 different grains, 150 malted barleys, a wild variety of second-fill barrels (that previously held tequila, maple syrup, port, mead and pinot noir), as well as innovative whiskey infusions such as cacao, mint, pecan and coffee.

Much like her contemporaries, she has also broken free from the Tennessean tradition of focussing on whiskey: Saul has released an amaro and an aquavit; Devin Walden – a platinum-filtered vodka; while at Gate Eleven Distillery in Chattanooga, wife-and-husband team Wanda and Bill Lee are rolling out their own take on rum, gin, agave and even absinthe.

“I think much of the spirit of rebelliousness and single-mindedness you find in the state can be traced back to those first Scots-Irish settlers,” says Wanda Lee, as she starts to cook a fresh batch of the ‘green fairy’. “Many were Presbyterians fleeing oppression by the English Crown. They were sick of being told what to do, so they came here and did as they pleased.” The absinthe mix begins to putter – a blend of wormwood, fennel, anis, with a touch of angelica root to balance out the flavours. “In Europe, angelica was a sacred herb, used to protect people from the bubonic plague,” says Lee, who tells me such knowledge comes from being a former school teacher, and jokingly adds that it was teaching middle-school children that turned her to drink. As I leave Lee to focus on the contents of her still, she tells me that after centuries of women contributing to the state’s distilling heritage, she believes the time has come for the ultimate accolade: a woman’s name taking its rightful place front and centre of the bottle – just like Jack Daniel, George Dickel or Jim Beam. “So, I’m planning a new gin that I will call Magdalena, after my great-grandmother,” she says. “It’s in honour not only of her, but all the women throughout history who have contributed to what makes Tennessee so special. The state wouldn’t be the same without us.”

‘THE JOB OF HEAD DISTILLER IS A MIX OF “MAGICIAN, ALCHEMIST, SCIENTIST AND ARTIST” ’

For more stories like this one, be sure to subscribe to our printed magazine.

Chris Stapleton performing Tennessee Whiskey at Austin City Limits in on 16 February 2018.

This track features on our Volume 7 playlist along with a variety of other tunes that serve as a great companion to this volume of TONIC. Check it out and subscribe to our Spotify channel to enjoy all of our playlists especially curated for our readers.